Can big data help you get a good night’s sleep?

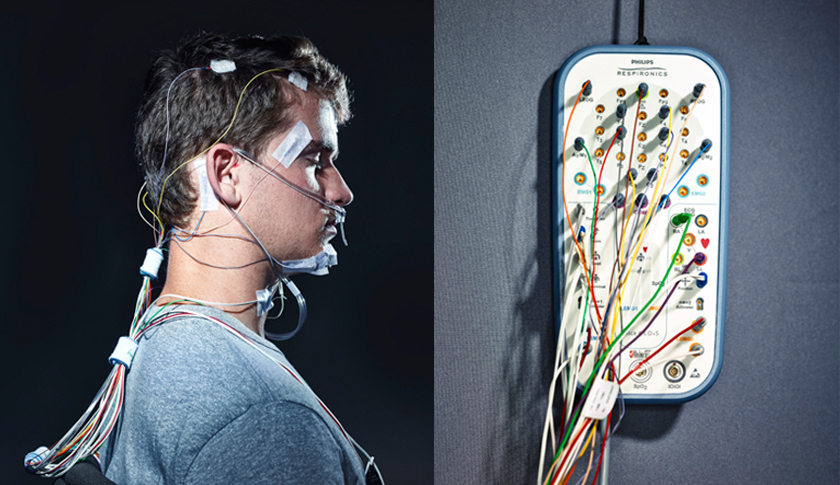

An employee of Fullpower Technologies, rigged for a sleep study in the company’s lab. Right: The “head box” transfers input from body sensors to a base station that processes the data to create a personal polysomnogram. Photographs by Ian Allen for Fortune

Large-scale computing power, combined with input from millions of fitness trackers, could help unlock the mysteries of our national insomnia.

I’m playing tennis with Marissa Mayer, and oddly, the Yahoo YHOO -2.07% CEO is wearing a pearlescent purple gown and sipping from a teacup. Her dress is just long enough to obscure her feet, so she appears to be floating across the baseline. As she strikes the ball, she tips her chin skyward and laughs in slow motion.

Meanwhile, I’m perched in the lotus position atop a manta ray that’s hovering above the ground like some kind of Landspeeder. And I’m panicking. How can I keep my balance and still hit the ball—especially with my shirt collar pulling at my neck the way it is? Can’t swing my racket. I jerk my head left. Then right. I claw at my jawline. The ball has cleared the net, and it’s headed my way. If only. I could. Just. Move. My head.

And poof. She’s gone. I open my eyes in a strange room. It’s pitch dark and completely silent, but I manage to find my bearings. Santa Cruz, Calif. Breathing heavily, I carefully disentangle a gaggle of wires twisted around my neck and roll over to glance at the clock. Just after 3 a.m.

This scene, I now know, was merely one of 18 REM-sleep interruptions that I experienced between 11:18 p.m. and 6:16 a.m. during one long February night. What a strange setting for the only dream I’ve ever had about a chief executive: in a laboratory, tethered to a byzantine apparatus designed to monitor my brain activity as well as every breath, eye movement, muscle twitch, and heartbeat.

Let me explain. Like you and probably everyone you know, I’ve always been confounded by my sleep routine. Why do I one morning rise ready to tackle the day and the next seem barely able to lift my head? How much rest can I be getting if I wake up sideways with the covers on the floor and my wife in the guest room? Most important, what can I do better? I don’t want a magic pill. I’ve tried those. I know the rules of thumb: less stress, more exercise, better diet, no afternoon caffeine, put down the damn phone. But I’d kill for a personalized formula.

So I subjected myself to a polysomnography test, or PSG, hoping to unravel some of the mysteries of the night. My procedure was administered in the offices of Fullpower Technologies, one floor down from where I had spent most of the evening talking with the company’s founder and CEO, Philippe Kahn.

A French expatriate who grew up in Paris, Kahn, 63, is a Silicon Valley oracle whose track record predates the web. He founded Borland Software (acquired by Micro Focus) MCFUF -1.09% in the mid-1980s, followed by Starfish software (Motorola) and LightSurf Technologies (VeriSign) VRSN -1.53% . In 1997, while anticipating the birth of his daughter, he paired a state-of-the-art Casio CSIOY 0.51% camera with a Motorola Startac and became, he claims, the first person to transmit a digital photo over cellular airwaves. He’s also been a leader in wearable technologies.

Philippe Kahn says Fullpower is “operating a huge sleep experiment unlike anything anyone has ever done.” Photograph by Ian Allen for Fortune

That’s precisely the focus of Fullpower, which licenses its software to other companies. Nearly five dozen framed patents for wearable-related software and devices hang on the wall in the company’s lobby. The oldest dates to 2005, long before tracking steps became such a phenomenon. In the conference room there’s an assembly of chairs and tables around a full-size bed, making obvious Kahn’s latest obsession.

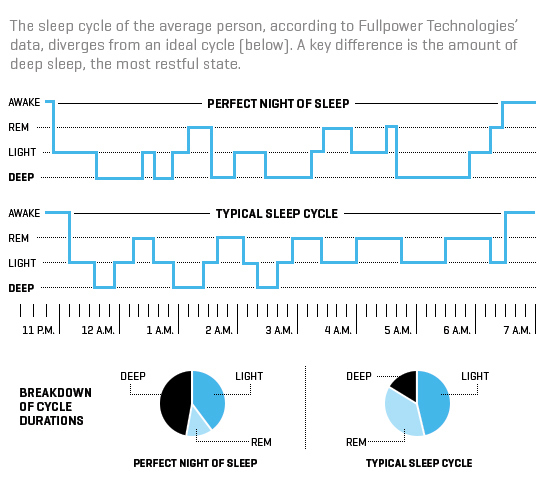

Fullpower built the lab about a decade ago to capture data from sleep patterns. Of course, test subjects don’t typically snooze deeply with wires glued to their skulls, chests, legs, and arms. But almost everyone manages to at least nod off for a while, and the data that subjects generate are valuable and often surprising. “What we found early on is that sometimes you sleep less and feel more refreshed,” Kahn says. “It’s because you woke up in the light part of the sleep cycle.” The insight led him to develop a sleep-cycle alarm that could determine the best time to alert a person within a certain window. “Sometimes it’s better to get up at 10 of seven than at seven,” he says.

Kahn insists that he’s on the cusp of many more such discoveries, and he’s intent on dispelling some of the conventional wisdom that stresses people out. “People say that if you can’t sleep for eight hours without waking up, something’s wrong with you. That’s such a fallacy,” he says. “Before electricity, people used to sleep in two shifts. That’s how I behave. Sleep for four hours, get up and do an hour and a half of work, and then another four.” He’s also skeptical of the notion that a quiet room is the best environment for shut-eye and dismisses the perceived deleterious effects of repeated rousing. “The sign of good sleep hygiene may not be how many times you wake up, but rather how rapidly you fall back to sleep. Sleep should be like hunger. Eat only when you’re hungry and until you’re satisfied.”

Fullpower has oceans of data to back Kahn’s theories. The company provides the sleep-tracking and activity-monitoring software for the Jawbone UP and Nike Fuel NKE -1.09% wearable devices as well as a new line of Swiss-made smartwatches and the forthcoming Simmons Sleeptracker Smartbed. The products transmit a mother lode of information (with users’ consent) to Kahn’s team. He thinks that by combining qualitative lab data and quantitative real-world data with machine learning, artificial intelligence, and other analytics technologies, he can unlock the secrets that so many of us walking dead are looking for: a better night’s sleep. “We’re operating a huge sleep experiment, worldwide, unlike anything anyone has ever done,” he says. “We have 250 million nights of sleep in our database, and we’re using all the latest technologies to make sense of it.”

Kahn is not alone. He’s part of a movement of brilliant entrepreneurs, data scientists, engineers, and academics who are looking at demographics, geographies, and lifestyles, and even into our genomes. They’re the beneficiaries of a historic explosion in sleep data, and they’re using many of the same technologies that are busily decoding some of the world’s other great mysteries. Tiny sensors, big data, analytics, and cloud computing can predict machine breakage, pinpoint power outages, and build better supply chains. Why not put them to work to optimize the most valuable complex system of all, the human body?

It’s not an exaggeration to say lack of sleep is killing us. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention calls it a public health epidemic and estimates that as many as 70 million Americans have a sleep disorder. Sleep deprivation has been linked to clinical depression, obesity, Type 2 diabetes, and cancer. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration estimates that drowsy driving causes 1,550 deaths and 40,000 injuries annually in the U.S. There are 84 sleep disorders, and some 100 million people—80% of them undiagnosed—suffer from one of them in particular: Obstructive sleep apnea, generally indicated by snoring, costs the U.S. economy as much as $165 billion a year, according to a Harvard Medical School study. That’s more than asthma, heart failure, stroke, hypertension, or drunk driving. And the study doesn’t account for tangential effects, like loss of intimacy and divorce. BCC Research predicts that the global market for sleep-aid products—everything from specialty mattresses and high-tech pillows to drugs and at-home tests—will hit $76.7 billion by 2019.

The financial upside for anyone who can crack the sleep code is obvious. And so the race is on. “I believe that 15 years from now, if we do this right, we can actually tackle epidemics like obesity, diabetes, and high blood pressure, and any number of lifestyle diseases,” says Kahn. “We’re going to help people live longer and better lives.”